Unconquerable, From Within and Without: Reading Howard Thurman

Some reflections on wrestling with Christianity and Jesus, a bunch of quotes, and some bits of synchronous inspiration

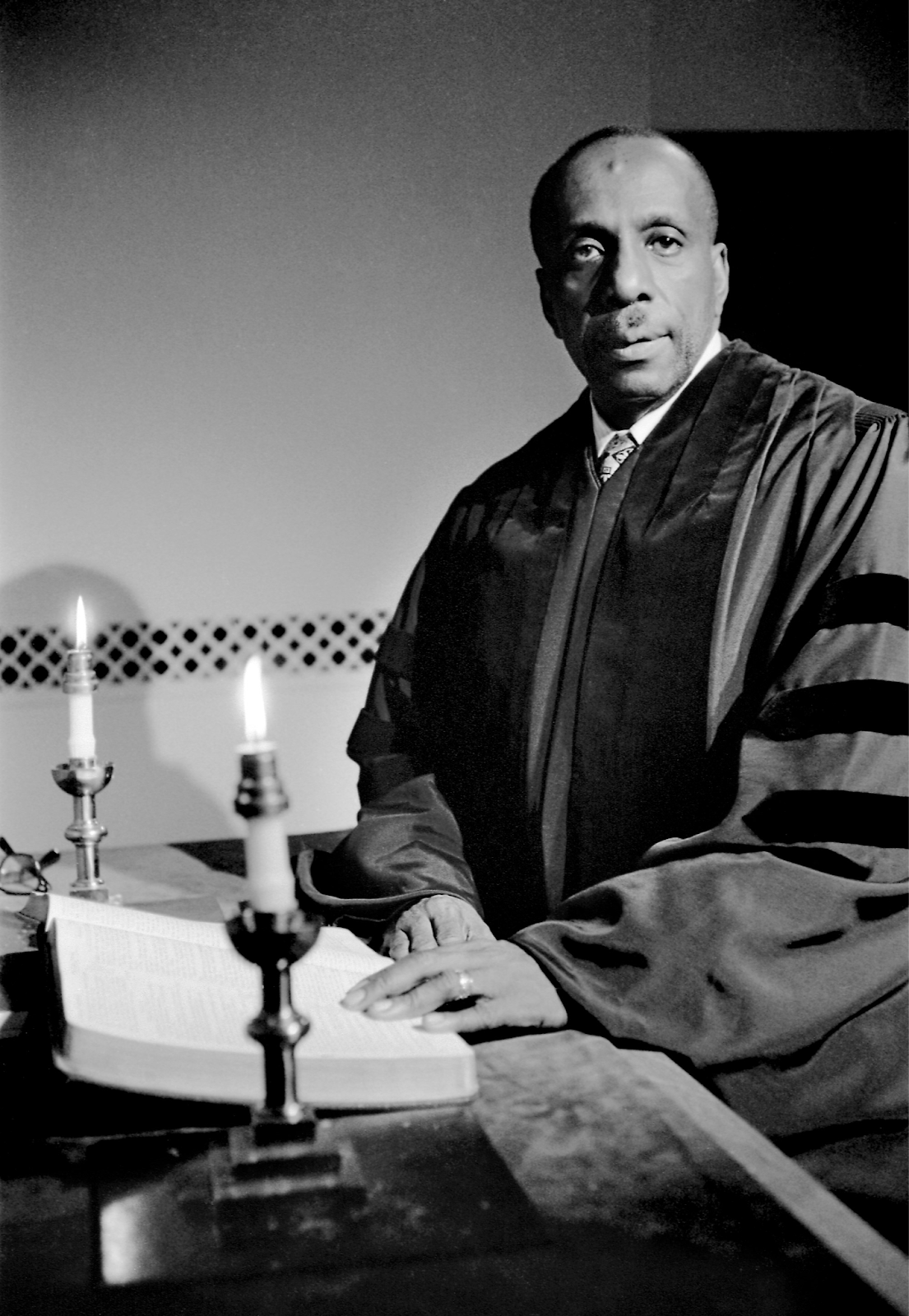

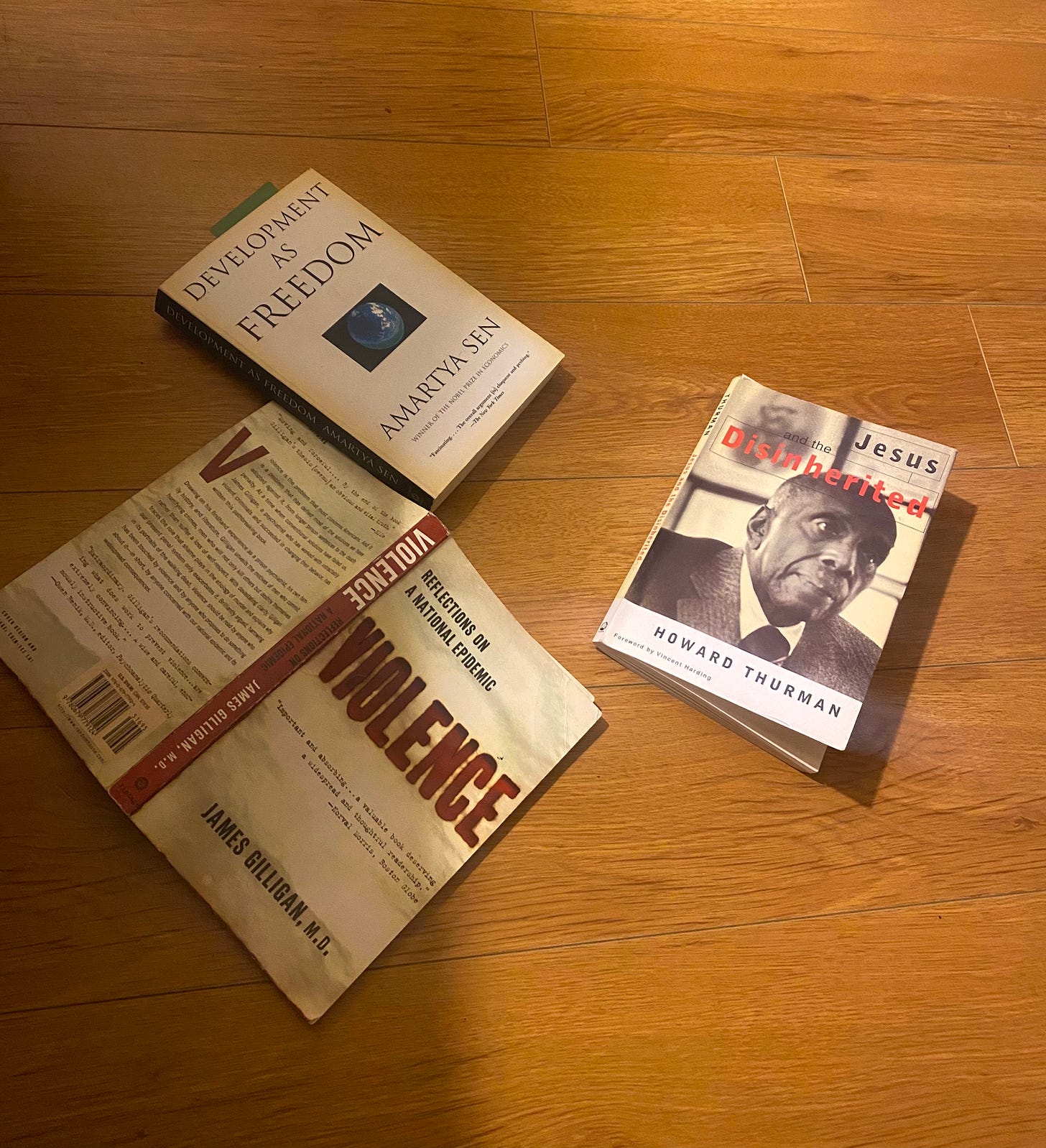

Jesus and the Disinherited, 1949 by Howard Thurman, a theologian and Christian “social mystic”, one who inspired Martin Luther King Jr.

Reflections on a National Epidemic, 1997 by James Gilligan, a psychiatrist who worked for 25 years in the American prison system and director for a hospital for the criminally insane.

Development as Freedom, 1999 by Amartyn Sen, an Indian economist whose emphasis on humanity in his economic theories changed the way we look at development in countries and measures of well-being.

What do the teachings of Jesus have to say to those who stand at a moment in human history with their “backs against the wall’” --- the poor, the disinherited, the dispossessed?

How might it be possible for human beings to endure the terrible pressures of the dominating world without losing humanity or forfeiting their souls?

These two questions are the central heartbeat of Howard Thurman’s novel, Jesus and the Disinherited (1949).

Howard Thurman (1899-1981) is a theologian and Christian “social mystic,” said to have inspired Martin Luther King Jr. It’s been said that King carried a copy of this book with him wherever he went. Before the Civil Rights movement began to churn some movement against tides of social and structural racism that held Black and other minority groups underneath a suffocating order until that point, Howard Thurman’s voice and philosophy rang out over the masses of folks who needed the strength to go on, lighting the hearts of those who would lead others closer to a collective dream of living in a world where everyone was a brother, or sister, where we had no reason to fear one another. He spoke of the truth of man needing a simple inner dream in one’s heart, for without one, he dies. He spoke of dreams often, not as childish or frivolous, but necessary in the most absolute sense. It is easy to see the fingerprints of Thurman on King’s message and life's work that the world so needed and still needs today.

From Jesus and the Disinherited:

“...the child of the disinherited is likely to live a heavy life. A ceiling is placed on his dreaming by the counsel of despair coming from the elders, whose experience has taught him to expect little and hope for less.

If, on the other hand, the elders understand in their own experiences and lives the tremendous insight of Jesus, they can share their enthusiasm with their children. This is the qualitative overtone springing from the depths of religious insight, and it is contagious. It will put into the hands of the child the key for unlocking the door of his hopes.”

I am reading this book as I wade through the remnants and untied ends of my own personal convictions about the relevance of Jesus’s teachings and Christianity in today’s world. As I grow older, moving through the continuous process of regathering and reshaping parts of my identity as new information and experiences pass through me, I have found myself wrestling with this more and more: Does Christianity have relevancy for me today? Is it useful or beneficial for the modern world? What does it mean for me? I find myself needing to articulate with a greater clarity, my spiritual practices and beliefs, so I can live them with greater sense of understanding and connection to all the humans that have been on this path before me.

As I opened the book to the the preface of Thurman’s book, I felt a kinship with his own curiosity that mirrored my own:

“Why is it that Christianity seems impotent to deal radically, and therefore effectively, with the issues of discrimination and injustice on the basis of race, religion, and national origin? Is this impotency due to a betrayal of the genius of the religion, or is it due to the basic weakness of the religion itself?”

He goes on, in Chapter 1, to acknowledge the way Christianity has aligned itself with the powerful throughout history, positioning itself with a missionary ideology.

“It has long been a matter of serious moment that for decades we have studied the various peoples of the world and those who live as our neighbors as objects of missionary endeavor and enterprise without being at all willing to treat them as brothers or human beings.”

I grew up in a Christian home, where the language of God through Jesus is what formed the sense of hope and belonging inside me as a little girl. My young fears, of the dark, of the unknown, of the fate of my familial circumstances, were held in an inner reservoir of belonging and safety that I could only call God. I prayed to Jesus, but my feelings of experiencing God wasn’t always necessarily connected to this idea of Jesus. I felt the feeling of God when I looked up to the sky, when I was underneath the protective umbrella of the large tree of our backyard, or at my bedside when I was most afraid of the dark and would sense angels beside me. But even then, when Jesus’s words were read to me, I would feel their importance.

In my college years, I grew disillusioned by what I saw as hypocrisy in the American Christian churches, which increasingly used the teachings of Jesus and the Bible as a tool to get wealthier, and to cast certain groups out, and others in. Since then, my thoughts about Jesus have felt like unfinished, unraveled ends. Donald Trump came into the presidency by my sophomore year of college, and by then, many American churches—broadly the Evangelical, mega-church-type that I grew up with—were preaching fear of the “other”. Essentially, the other groups were to blame for the world’s current state of wickedness. This feeling of misalignment with the tone and content of these messages, along with my self-study of the psychology of cults and mind control, led me to drift away from the roots of my religious upbringing. It became all too clear—both in the church and politically–that fear was being used as a weapon to control. I began to seek other ideas, expressions, and methods of seeking God. I began drawing closer to environments and idas that knew to be true—that there is no fear in love, that perfect love casts out fear.

I found myself increasingly drawn to types of churches that I hadn’t grown up with—those like the Episcopalians, whose services revolved around old liturgies and the Eucharist. I found a new beauty and solace in the ritual of kneeling beside strangers for the Eucharist as I accepted wine and bread, and in the words that hung over us as we made our way to the altar and shaped that possibility: that everyone is welcome to this table to share in the body and blood, and that we are one.

Reading through Howard Thurman’s book, and listening to original recordings of his sermons preached at the Fellowship Church of San Francisco (the first racially integrated, intercultural church in the nation) has been a gift like an anchor of hope.

I am 28 now, settling into the mundanity of adult life, closer to the visceral experience of what it takes to survive in this world. I have been in the stream of the every day experience for about 6 years now, the “day-in and day-out” of the average adult life that David Foster Wallace refers to in his Kenyon commencement speech, the “whole, large parts of adult American life that nobody talks about in commencement speeches…. boredom, routine, and petty frustration.” I find myself, like us all, in the throes of the minute daily back-and-forth negotiations in one's mind that make the difference between hope alive and lost. If I let myself go long enough, my attention will be like a sticky piece of tape dropped in a pile of dust, picking up bits of crap that come out as complaints, moodiness, frustration, and an overall cloud of dissatisfaction about the state of life.

For this reason, and the current power dynamics at play in the larger system in America right now, I’ve been drawn to Thurman’s words. The systems that govern us are increasingly grouping more and more people, including my own peers, into the group of “the disinherited”, those who are the subject of Thurman’s inquiry. I’ve seen friends around me, the people I work with, and others slowly sapped of their inspiration. A million acute and invisible pressures and violences threaten and do put out the small embers of inner dreams. We are witnessing the growing effects of structural violences, killing people in mass through wars and genocide, and slower violent forces, like inaccess to proper medical treatment due to poverty. The other book I am reading pictured above is, “Violence: Reflections on a National Epidemic” by James Gilligan, M.D, which contains intertwining insights with Thurman’s message. He defines structural violence as follows:

“Structural violence differes from behavioral violence in at least three major respects:

1) the lethal effects of structural violence operate continuously, rather than sporadically, whereas murders, suicides, executions, wars, and other forms of behavioral violence occur at one time

2) Structural violence operates more or less independently of individual acts; independent of individuals and groups (politicians, political parties, voters) whose decisions may nevertheless have lethal consequences for others

3) Structural violence is normally invisible, because it may appear to have had other (natural or violent) causes.”

As billionaires and others continue to shovel wealth and power into their own respective piles, the groups at the bottom and around the sides—-those at risk of inquiry, death, psychological harm, and deprivation due to these larger structural and political decisions—grows. In my job as a grant writer for human services nonprofits, I see closely the effects of budget cuts on the underresourced. It has not all unfolded yet, but what is on the horizon feels foreboding. Thurman’s message, written in 1949, is as contemporary and alive as ever in our current circumstances.

So I have needed this anchor. Perhaps you do to. The continuous thread through all of Thurman’s work is the validation of the inner dream as a source of refuge and purpose that cannot be touched by externalities, or even the moments of self-doubt and disbelief that afflict our human experience from time to time.

The elevation of Jesus’s central message through Thurman is a reminder that hope is no small and weak endeavor. We are increasingly becoming people who “need the profound succor and strength” to “live in the present with dignity and creativity.” Whatever this means to you—whatever spaces, places, people, ideas grow your hope—linger longer there. It’s oxygen.

“Nothing less than a great daring in the face of overwhelming odds can achieve the inner security in which fear cannot possibly survive. It is true that a man cannot be serene unless he posses something about which to be serene.

Here, we reach the watermark of prophetic religion, which is the essence of Jesus of Nazareth's religion.

Of course, God cares for the grass of the field, which lives a day and is no more, or the sparrow that falls unnoticed by the wayside. He also holds the stars in their appointed places and leaves his mark in every living thing. And he cares for me!

To be assured of this becomes the answer to the threat of violence—yea, to violence itself. To the degree to which a man knows this, he is unconquerable, from within and without.” - Jesus and The Disinherited, Howard Thurman

Recent inspiring art and finds:

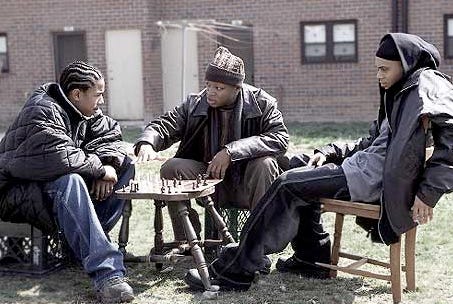

1. I just finished Season 1 of “The Wire” (on HBO Max). It was truly a synchronous learning moment alongside my reading of these books. The Wire premiered in 2002, and it is an incredible social commentary of our modern systems. The realistic portrayal of institutions, groups of people, and individual motivations casts into a clear light how the layers of power lead to violent and tragic consequences for the least powerful.

Howard Thurman’s collection of sermon recordings from the Fellowship Church of San Francisco. I felt like I had struck a goldmine when I found these. Howard Thurman’s family donated these recordings, which are now public and part of the Howard Thurman Digital Archive, housed at Pitts Theology Library, Emory University. The fact that the public has access to these is incredible a baffles me! Great way to get a sense of Thurman’s work.

Until next time, thank you so much for reading and take care :)

If you would like to purchase the books mentioned in this post, consider using this affiliate link to Bookshop.org to support the work of The Prison Library Project. A portion of your purchase will be dedicated to supporting the work of sending books to prisoners in 400 state and federal prisons and detention centers throughout the United States.